Epidemiology

Mgr. Hana Celušáková, PhD.

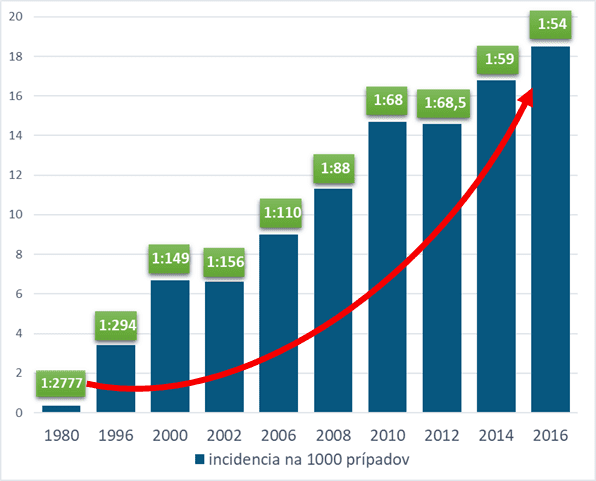

As shown in graph no. 1, the prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) in the United States is steadily rising, from 1: 294 in 1996 to the current reported prevalence of 1:54 in 2016. International research initiated by the WHO reports a lower prevalence of the disease in the population compared to the United States, in the ratio of 1 in 132 children born (Baxter et al., 2015) – which is still a significant increase in recent decades. In Slovakia, the prevalence of ASD is not being systematically monitored, so we are not aware of the precise occurrence of this disease in our country; it is assumed, however, that it will correspond to data from other developed countries. The increase in the incidence of this disease in the Slovak population is also evidenced by the growing demand for quality diagnostics and evidence-based intervention for individuals with ASD..

Prevalence – incidence of Autism Spectrum Disorders in the population according to CDC

The causes of the increasing incidence of ASD are not fully understood, but scientific studies suggest that this is a combination of several factors. These are not only biological and environmental causes, but changes in the understanding of the diagnosis are also important – research is refining and expanding diagnostic criteria and improving the validity of diagnostic tools.

Changes in diagnostic criteria from DSM II / ICD-8 to DSM-5 / ICD-11

The first important factor in the increase in the prevalence of ASD is changes in the understanding of the diagnosis and the expansion of diagnostic criteria.

Autism was first described independently and practically simultaneously by Kanner in 1943 and Asperger in 1944. Although nearly three-quarters of a century have ASDsed since the first description of the disease, intensive research in the field of autism spectrum disorders started to be conducted only in the recent decades. In ICD-8 (1967) and DSM II (1968) , autism was not understood as a separate diagnosis, it was included under schizophrenic diseases – as a childhood type of schizophrenia.

The diagnosis was first included separately in the classification systems only about 35 years after the first description by Kanner and Asperger. In DSM III (APA 1980) called Childhood Autism, it belonged to Pervasive Developmental Disorders. Child autism has already been mentioned in ICD-9 (WHO 1977), although it continued to be classified under Childhood-onset Psychoses, along with Disintegrative Psychosis. The diagnostic criteria at that time were closest to the diagnosis of childhood autism as it was described by Kanner (1943). The rate of symptoms and disabilities was significant, these were children with delayed speech, low communication skills, mostly with mental disabilities, motor stereotypes, strictly and narrowly defined interests.

In the next revision of the DSM-III -Rfrom 1987, Pervasive Developmental Disorders already includes Autistic Disorder and Pervasive Developmental Disorder, otherwise unspecified (also known as PDD NOS). It is worth noting that in this revision, autism is no longer associated exclusively with childhood, and the name begins to reflect the lifelong effects of this disease on the functioning of the individual.

In DSM-IV (APA, 1994) and ICD-10 (WHO 1992), Pervasive Developmental Disorders has already included e.g. Asperger’s syndrome and other diagnoses, which pointed to the fact that autistic manifestations may also manifest in children without mental disabilities or impaired speech development (Constantino and Charman, 2016), so that more and more individuals met the diagnostic criteria.

Currently in force in Slovakia, the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (CD-10) (MKCH-10) – classifies autism under Pervasive developmental disorders and includes the following diagnoses in this group:

- childhood autism,

- atypical autism,

- Asperger’s syndrome,

- Rett syndrome and

- other disintegrative disorders.

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of the 5th Revision (DSM-5), used in the USA since 2013, all these diagnoses were included under one umbrella term – Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD).

In the summer of 2018, the World Health Organization (WHO) published the 11th revision of the International Classification of Diseases – ICD-11. . It is currently being translated and implemented in Europe, and it is expected to be put into practice on January 1, 2022. In MKCH-11, similar to DSM-5, the distinction between individual diagnoses such as childhood autism and Asperger’s syndrome is not used anymore and an umbrella term is applied – Autism spectrum disorders.

Autism spectrum disorders according to individual classification systems and their revisions

| ICD – 10 | ICD – 11 | DSM-IV-TR | DSM-5 |

| Childhood autism | ASD without impaired intellectual development with little or no impairment of functional speech | Autistic disorder | Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) Specifications are provided, namely: severity,presence of mental retardation, speech disorder,possible comorbidities |

| Atypical autism | ASD with impaired intellectual development and with mild or no impairment of functional speech | Pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified | |

| Asperger’s syndrome | ASD without impaired intellectual development and with impaired functional speech | Asperger’s disorder | |

| Rett syndrome | ASD with impaired intellectual development and with impaired functional speech | Rett disorder | |

| Other disintegrative disorders | ASD without impaired intellectual development and with absence of functional speech | Childhood disintegrative disorder | |

| ASD with impaired intellectual development and with absence of functional speech |

Improving screening and diagnostic tools

The second factor influencing the increase in ASD prevalence is the improvement and refinement of screening and diagnostic methods. The need for effective ASD screening has led to intensive research into the first signs of autism at the youngest possible age (Zwaigenbaum et al. 2013). Retrospective, but most importantly prospective studies not only deepen the knowledge about the development of the disease and the first symptoms, they also improve the sensitivity of specialized experts to the early manifestations of ASD. Screening methods also increase awareness of the disease among paediatricians and parents. Also standardized diagnostic methods (e.g. Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule – Second Edition (ADOS-2), or Autism Diagnostic Interview – revised (ADI-R)contribute to accurate diagnosis and help quantify the degree of disability, but they also bring consensus into the professional discussion of the symptoms of the disease, which reduces the risk of misdiagnosis.

Raising awareness of ASD among professionals as well as the general public improves the detection of the disease. It is also important that there is a de-stigmatization of mental illness and sometimes even idealized depiction of ASD in works of art, which reduces parents’ fears about starting the diagnostic process in children with mild disabilities. In some countries, the diagnosis of ASD is the key to easier access to intervention and various reliefs, support and help in the social and school system, so parents are more motivated to seek out/confirm the diagnosis of their child.

Last but not least, it is important to critically evaluate data collection methods in population studies. In those where data are collected from both health and educational institutions, the incidence of the disease may increase due to partial cohort overlap.

Environmental and biological factors

On the other hand, it is important to examine the environmental and biological factors influencing the increase in the incidence of the disease. Environmental risk factors include increased parental age, too short or long periods between pregnancies, use of certain drugs or recreational drugs during pregnancy, exposure of pregnant women to increased levels of chemicals in the environment, but also higher levels of air pollution, malnutrition in pregnancy, infection during pregnancy, family burden of immune diseases, low gestational age and preterm birth (Lyall et al. 2017).

Literature:

- American Psychiatric Association. (1980). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3th ed. Washington DC.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders 5th ed. Washington DC.

- Asperger, H. (1944). Die “Autistischen Psychopathen” im Kindesalter. Archiv fur Psychiatrie und Nervenkrankheiten, (117), 76–136.

- Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network Surveillance Year 2000 Principal Investigators & Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2007). Prevalence of autism spectrum disorders—Autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, six sites, United States, 2000. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Surveillance Summaries (Washington, D.C.: 2002), 56(1), 1–11.

- Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network Surveillance Year 2002 Principal Investigators & Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2007). Prevalence of autism spectrum disorders—Autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 14 sites, United States, 2002. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Surveillance Summaries (Washington, D.C.: 2002), 56(1), 12–28.

- Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network Surveillance Year 2008 Principal Investigators & Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2012). Prevalence of autism spectrum disorders—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 14 sites, United States, 2008. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Surveillance Summaries (Washington, D.C.: 2002), 61(3), 1–19.

- Baxter, A. J., Brugha, T. S., Erskine, H. E., Scheurer, R. W., Vos, T., & Scott, J. G. (2015). The epidemiology and global burden of autism spectrum disorders. Psychological Medicine, 45(3), 601–613.

- Constantino, J. N., & Charman, T. (2016). Diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder: Reconciling the syndrome, its diverse origins, and variation in expression. The Lancet Neurology, 15(3), 279–291.

- Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network Surveillance Year 2010 Principal Investigators & Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2014). Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years—Autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2010. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Surveillance Summaries (Washington, D.C.: 2002), 63(2), 1–21.

- Christensen, D. L. (2016). Prevalence and Characteristics of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2012. MMWR. Surveillance Summaries, 65. Cit apríl 24, 2017, z http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/ss/ss6503a1.htm

- Kanner, L. (1943). Autistic disturbances of affective contact. The Nervous Child, (2), 217–50.

- Lyall, K., Croen, L., Daniels, J., Fallin, M. D., Ladd-Acosta, C., Lee, B. K., Park, B. Y., et al. (2017). The Changing Epidemiology of Autism Spectrum Disorders. Annual Review of Public Health, 38(1), 81–102.

- Maenner, M. J. (2020). Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2016. MMWR. Surveillance Summaries, 69. Cit október 22, 2020, z https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/ss/ss6904a1.htm

- Ousley, O., & Cermak, T. (2014). Autism Spectrum Disorder: Defining Dimensions and Subgroups. Current developmental disorders reports, 1(1), 20–28.

- World Health Organisation. (2019). ICD-11—International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision. Https://icd.who.int/en/. Cit január 28, 2019, z https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http%3a%2f%2fid.who.int%2ficd%2fentity%2f437815624

- World Health Organisation. (1992). ICD-10 Classifications of Mental and Behavioural Disorder: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organisation.

- Zwaigenbaum, L., Bryson, S., & Garon, N. (2013). Early identification of autism spectrum disorders. Behavioural Brain Research, SI:Neurobiology of Autism, 251, 133–146.